The global economy avoided what could have been a systemic debt crisis during the turbulence of recent years, but vulnerabilities remain amid high debt servicing costs that pose an important challenge for low and middle-income countries. Some may yet confront major tests.

When countries do falter on debt, restructuring is critical to containing the damage. Restructuring should be as quick as possible because delays deepen distress by making adjustment harder and adding to the costs for both debtors and creditors. Longer waits leave people suffering when they lose jobs and face increasing poverty, while creditors watch their losses mount as they wait for recovery. It’s a lose-lose situation.

While some sovereign restructurings have faced significant delays, we are working with our counterparts to accelerate the process. The progress achieved so far shows how the world can work together to reduce risks.

Common Framework has started to deliver

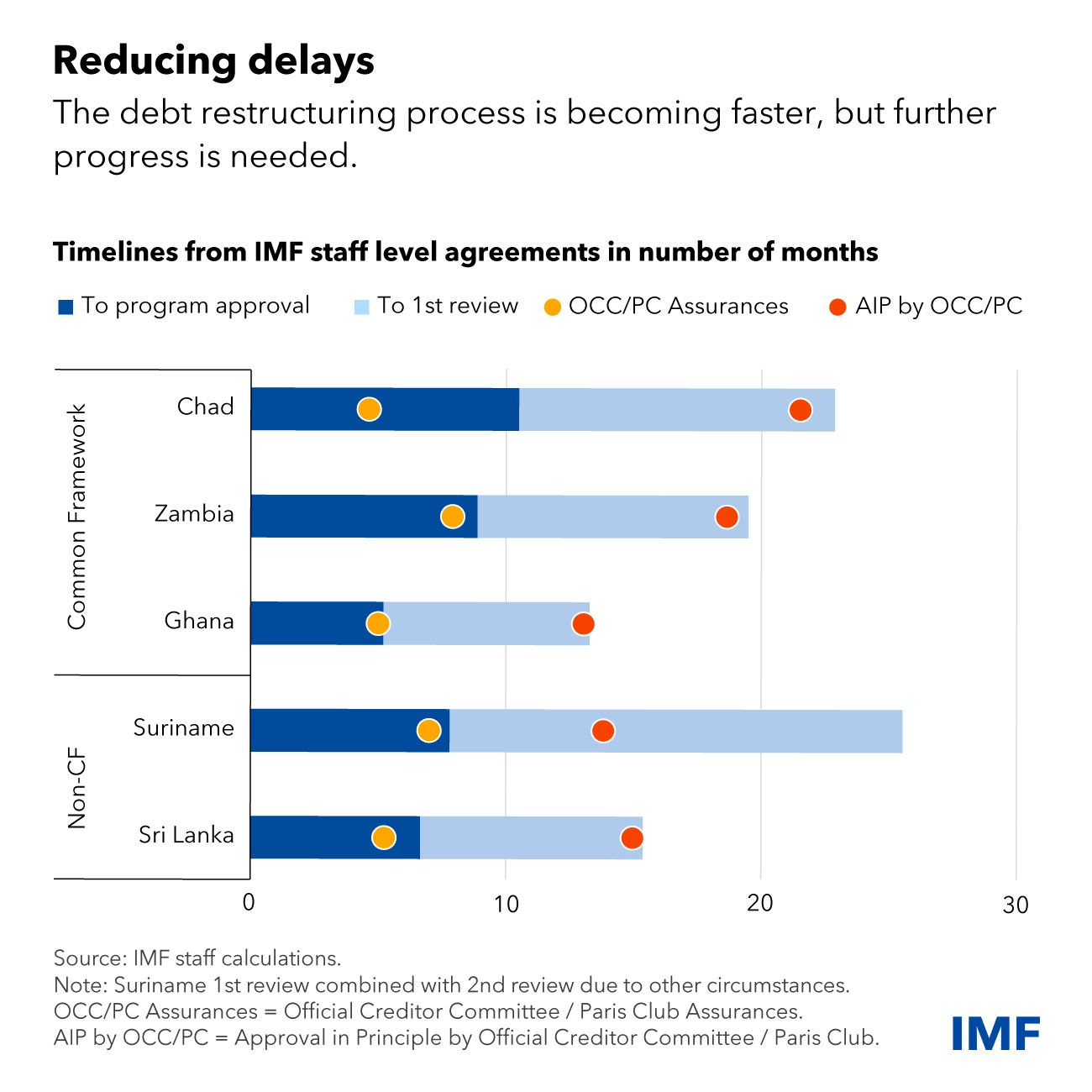

The Common Framework, which brings creditor countries together to help restructure debt where needed, has started to deliver. How? By reducing the time from IMF staff level agreement – a key step toward an IMF program – to delivering the financing assurances from official creditors required for program approval. This means that the Fund can move in more quickly to provide much needed financial assistance to the country. For example, Ghana’s agreement this year took five months to cover those steps, roughly half the time it took for Chad in 2021 and Zambia in 2022. Ethiopia’s talks are likely to be faster, closer to the customary two or three months.

These improvements are possible in part because stakeholders have developed more experience working together, including with non-traditional official creditors like China, India, and Saudi Arabia. Earlier cases presented creditor coordination challenges. But becoming more familiar with the process helped parties better know what to expect, building trust, and allowing creditors to overcome more easily what had previously been stumbling blocks.

We are also seeing progress in accelerating debt restructuring for emerging market countries outside of the Common Framework. Sri Lanka’s case was faster than the process for Suriname that preceded it in 2021, reflecting improvements in creditor coordination and improved understanding of safeguards and assurances.

Global Sovereign Debt Roundtable has been effective

The IMF, World Bank and the Presidency of the Group of Twenty introduced the Global Sovereign Debt Roundtable (GSDR) early last year to help overcome various disagreements on technical issues. Discussions among creditors and debtors have made progress on several key aspects, including comparability of treatment among creditors, defining what debts are included in the restructuring, information sharing, and processes and timelines. This has helped accelerate ongoing restructuring cases and build good foundations for the future. That progress, summarized in a recent report, is a big step forward.

IMF is reforming its debt policies

The IMF is building on our sovereign debt restructuring experience to make the process even faster. The Executive Board in April adopted significant reforms to our debt policies:

- They provide tools that generally would allow IMF program approval within two or three months of a staff-level agreement, including through safeguards that help us proceed in cases where there are coordination problems among creditors. Approval in principle for programs, which enables disbursement as soon as financing assurances materialize, will increase transparency and help complicated cases move along on such a schedule.

- They create a new procedure for establishing financing assurances, which should provide greater flexibility over time. Accordingly, the Fund would assess that a “credible official creditor process” is underway, based on actions by the creditors and accounting for the creditor’s track record in delivering. This will eventually be considerably faster than the present practice of waiting for formal letters.

These reforms will facilitate faster engagement with the debtor country—a key step since delays can intensify a crisis. The reforms will also provide more information to creditors to help them reach restructuring decisions faster (either because the program can be approved more quickly, or through approval in principle). This would include information about our economic projections, policy commitments, and our debt sustainability analysis. This complements other Fund efforts to improve transparency and share information in a timely manner with all stakeholders involved in the restructuring process.

High geopolitical tensions have made global economic cooperation more difficult. Yet we can take heart from the fact that creditors and Fund shareholders more broadly are coming together unanimously to assist countries that need debt restructuring. This is critical to further improve the international debt architecture which is a key priority, especially given the high debt levels and prohibitive debt servicing costs in some countries.

What’s next

As we strive to reduce delays, it is important to note that sovereign defaults and requests for comprehensive debt relief have tapered off since 2021 and 2022. The last notable request was Ghana’s more than a year ago. Markets have reopened earlier this year for low-income countries, with Benin, Cote d’Ivoire, Kenya, and Senegal having raised money from foreign investors. Emerging market bond spreads are back to pre-pandemic levels, signaling investor confidence that those countries can repay debt.

However, spreads for about 15 percent of emerging markets are at distressed levels, underscoring vulnerability. Likewise, low-income countries still need to refinance about $60 billion of external debt each year over the next two years—about triple the average in the decade through 2020. Around 15 percent of low-income countries are in debt distress and another 40 percent are at high risk of distress.

So, progress on debt must continue. The GSDR will continue to address remaining key restructuring challenges such as how official and private creditor processes can move in parallel, and ways to address liquidity challenges. This could involve a potential menu of options for countries including the use of the Common Framework for coordinated liquidity relief; liquidity management operations such as debt swaps or buy backs; and ways to support new inflows including through risk-sharing instruments.

The IMF will distill our policies in a sovereign debt handbook that we plan to publish later this year. This clarity should further underpin more efficient processes. We are also reviewing the debt sustainability framework for low-income countries, jointly with the World Bank, to ensure it remains fit for purpose.

Easing the liquidity squeeze

More will be needed to address debt challenges and avoid distress amid elevated interest rates and financing needs, against a backdrop of enormous long-term financing needs for economic development and to cope with climate change.

Borrowing countries, creditors, and the international community have roles to play. Borrowers must foster economic growth and boost government revenues so that they can create space to finance development and climate-related spending while maintaining debt on a sustainable path. Given that policy reforms in borrowing countries will take time to deliver results, official creditors should consider mobilizing more funding at reduced cost, particularly grants. The Fund will continue to help support these efforts and provide adequate financing, including through the review of our concessional facilities.

A forthcoming blog will elaborate on how the international community must keep working together to help ease the burden of borrowing and alleviate the liquidity squeeze facing many emerging and low-income countries.